By Doug Boilesen, 2014

The following Lincoln Journal

Star newspaper article was written by Nancy Hicks in 2013

and is a good summary of John Johnson's photographs that he

took in Lincoln, Nebraska between 1910 and 1925 and how some

of Johnson's glass negatives ended up as photographs in the

National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington,

D.C.

Axel Boilesen and his son Doug

originally obtained these glass negatives after placing an ad

in the Lincoln Journal Star and receiving a call that

took them to a house that had some phonograph related items.

The following story is included with Axel's Friends of the

Phonograph stories because Axel and Doug purchased these

glass negatives, 'transferred' them to neighbor and friend Doug

Keister (a.k.a. DK) while retaining only one glass negative

with the Edison phonograph and little girl in it. DK's friendship

would be maintained through the decades and his caretaking of

those negatives and efforts to promote the legacy of John Johnson

are described in the following 2013 newspaper article.

This little girl

stands proudly for her portrait next to an Edison C-150 Sheraton

design phonograph. This Edison disc phonograph 'was introduced

in June 1915 and manufactured until 1918. It was a very popular

model and became Edison's second-best seller in 1917."

(1) The photograph was

taken by John Johnson in Lincoln, Nebraska circa 1920.

Century-old pictures of black

Lincolnites to hang in new national museum

August 05, 2013 4:00 am • By NANCY

HICKS / Lincoln Journal Star

This story of discovery began

with an article in the Lincoln Journal Star about 36

stunning photographs.

And it ends with the likelihood

that pictures of Lincoln residents from the early 1900s -- black

Lincolnites featured in the work of a black photographer --

will hang in the new National Museum of African American History

and Culture in Washington.

“It’s one of those 'Antiques Road

Show' kind of stories. Even better,” said Doug Keister, a Lincoln

Southeast graduate who, for decades, saved heavy boxes of glass

negatives he bought in Lincoln as a teenager.

They turned out be an artistic

and historic treasure.

In May 1999, former Journal Star

reporter Clarence Mabin wrote a story about 36 glass negatives,

beautiful photographs of Lincoln’s black community in the early

1900s, taken by an unknown photographer.

“I was expecting some amateur

work, and these pictures just knocked me for a loop. So well

proportioned, such a brilliant use of space and sense of composition,

such amazing rapport with his subjects," John Carter, historian

for the Nebraska Historical Society, said in that story.

"It’s obvious he’s doing more

than just taking a picture. He’s doing portraiture. And social

commentary.”

Mabin’s article led to the discovery

of Keister’s collection of several hundred pictures, taken in

Lincoln roughly between 1910 and 1925 by photographer John Johnson.

Keister, a photographer, author

and Lincoln native, has donated 60 large-scale prints made from

that collection to the new museum, due to open on the National

Mall in 2015.

“They speak to a time and a place

where African Americans were treated as second-class citizens

but lived their lives with dignity,” museum curator Michele

Gates Moresi said about the exhibition in an article in the

February 2013 Smithsonian Magazine.

For decades, the photos were simply

a heavy load that Keister carted from house to house, taking

up valuable storage space.

Keister got the glass negatives

from friend Doug

Boilesen and his father, Axel, who bought the negatives

from a Lincoln family during their search for antiques, including

an Edison phonograph, the “holy grail of phonographs,” Keister

said.

One of the negatives was of

a girl standing beside an Edison phonograph.

Keister bought the boxes for $15.

Keister printed some of the negatives

-- O Street, construction of the Miller & Paine building and

the post office (now the Grand Manse) -- and sold them to local

history buffs like Jim McKee, years before anyone recognized

the value of the entire collection.

And Keister took the boxes with

him when he moved to California, continuing to cart them around

the state as he moved.

In 1999, Keister’s mother, Kay

Keister, clipped and sent the Journal Star story about the 36

negatives to her son. She remembered he also had some glass

negatives, so she thought he might be interested.

Keister realized his were likely

the work of the same photographer.

He brought his boxes, containing

almost 280 glass plates, back to his hometown and met with Lincoln

historian Ed Zimmer.

Since then Zimmer, a historical

sleuth, has identified the photographer, put names to some of

the faces and Lincoln locations, and found more negatives and

pictures, 400 to 500 of them: the Keister collection plus others,

many saved by descendants of those photographed.

History Professor Jennifer Hildebrand

has used the pictures as examples for an article on the New

Negro Movement, a precursor to the Harlem Renaissance.

In an era when black Americans

faced severe discrimination, "new Negroes evinced pride in self,

in their African heritage, and in the color of their skin. Often

the images that they shaped convey a great sense of confidence,

strength and determination," Hildebrand, an associate professor

of history at the State University of New York, Fredonia, wrote

in a 2010 Nebraska History Quarterly.

"The beauty of the black race

and the shared goals and aspirations of white and black Americans

were at the heart of the NNM," she wrote.

The 36 plates that were the focus

of Mabin's story were discovered as University of Nebraska-Lincoln

graduate student Kathryn Colwell was researching historic black

landmarks in the city and interning with Zimmer.

Ed Wimes, now an executive vice

president at UNL, told her about the plates, owned by the McWilliams

family, information she passed on to the Historical Society's

Carter.

Carter went to the home of Victor

and Juanita McWilliams to see the negatives.

They were in a Harley-Davidson

boot box, he remembers, the negatives carefully separated by

kitchen towels.

Carter picked up the first one,

he said: "And it wasn’t a good photograph, it was a phenomenal

photograph. The hair stood up on the back of my neck.

"I picked up the next one --

and next one -- all were just phenomenal."

Mabin, who now works in the Legislature’s

performance audit office, had seen prints of some of the pictures

when he interviewed Art McWilliams Sr. in 1989 for a story about

the McWilliams family's long history in Lincoln. He remembers

instinctively knowing that they were extraordinary pictures.

The photographer, Zimmer concluded,

was John (Johnny) B. Johnson, an 1899 graduate of Lincoln High

School who briefly attended the University of Nebraska, where

he played football.

In an era when black Americans

were not hired by white businesses for anything other than menial

labor, Johnson was a janitor at the federal building, drove

a wagon and photographed Lincoln's small black community.

Johnson was born in 1879 to Harrison,

a Civil War veteran, and Margaret Johnson, both former slaves.

He married late and lived most of his life in a home built by

his father at 1310 A St.

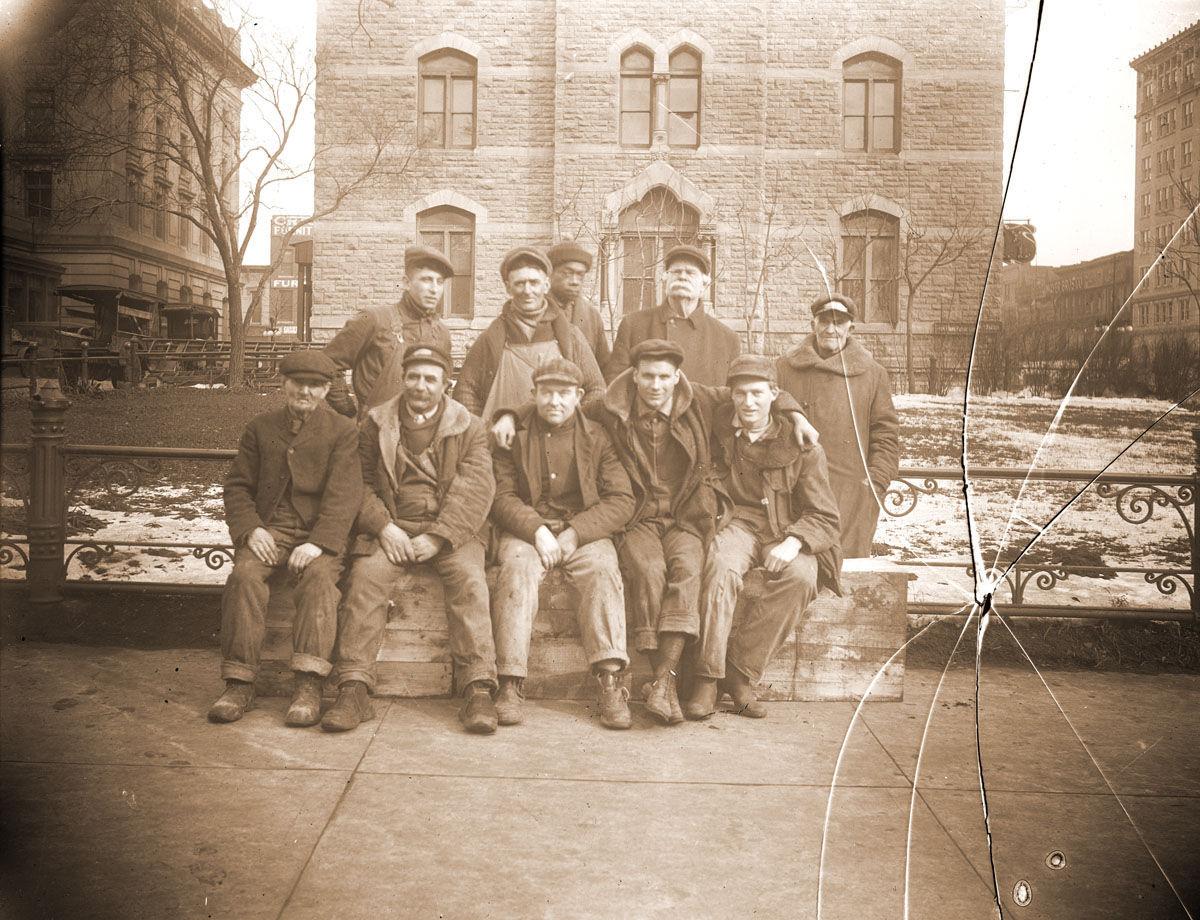

Some of the photos appear to be

commissioned portraits. Others feature co-workers, family and

friends. And some show Lincoln architecture, construction sites

and the men who worked there.

Some are elegant portraits, with

the families of Lincoln's black leaders at the time -- the McWilliamses,

Malones, Deans, Talberts, Burckhardts, Williamses -- among the

subjects.

In addition to their beauty, the

photos have historical significance because there are so few

photographs from the era depicting African Americans in small-

and medium-size towns taken by a black photographer.

Keister calls them a “rare glimpse

into the everyday lives of an African-American community on

the Great Plains.”

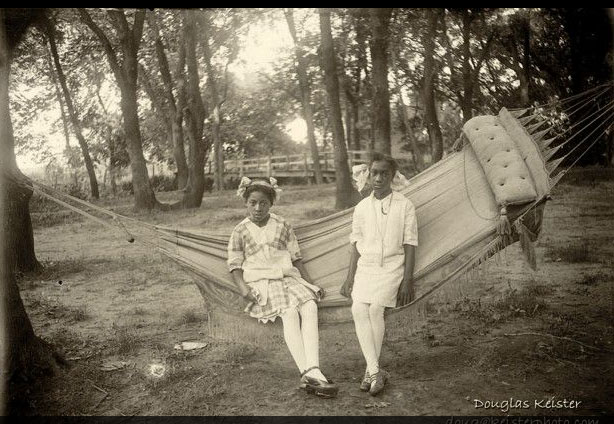

The young lady on the right

is Florence Jones (later Clark). Her companion has not been

identified. Jones was a student at Park and McKinley elementary

schools and Lincoln High School, graduating in 1923. The photograph

is among many taken in Lincoln on black and white glass negatives

by African-American photographers John Johnson and Earl McWilliams

between 1910 and 1925. 2001 Backyard picnic Mother's touch Baseball

player Florence Jones and companion

This photograph was taken on

the front porch of a house that still stands at 715 C St. in

Lincoln. At the time Cora and Alonzo Thomas ran a grocery store

in the front room of the home. Four of the Thomas children and

two friends are in the photo. The baby is Lonnie Thomas, born

in 1909, who became a championship golfer. Lonnie’s daughter

Deborah Thomas was a backup singer for several groups including

Lionel Richie and Diana Ross. The little white girl at the side

is Marie Busch, who lived next door at 703 C St., the daughter

of Germans from Russia immigrants. JOHN JOHNSON, Courtesy

Douglas Keister

Mamie Griffin, who worked as

a cook, lived at 915 U St. in 1914 with her husband, Edward,

a waiter at the Lincoln Hotel. Their little house and other

humble residences stood on a dirt street among railroad tracks

and industrial uses north of downtown Lincoln. Far from humble

are the dress and demeanor of this woman, posing confidently

with her romance novel, "The Wife of Monte Cristo." JOHN JOHNSON,

Courtesy Douglas Keister

Two women show off their pit

bull terrier, circa 1910-25. JOHN JOHNSON, Courtesy Douglas

Keister

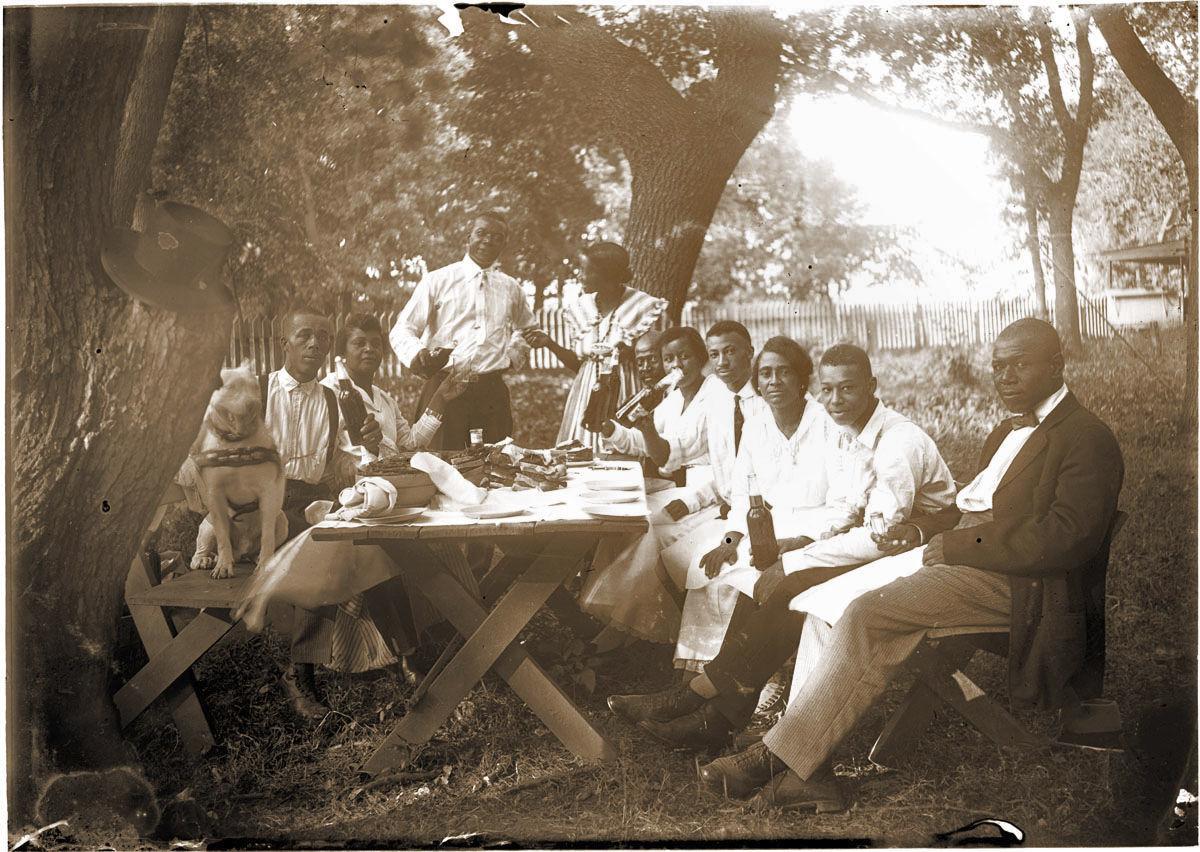

In this photo by John Johnson

of Lincoln, 10 people and a dog share in a backyard picnic,

circa 1910-25. The scene appears casual, but the picnic benches

have been angled out from the table to allow each person to

be seen, and to lead the eye to the couple serving as host and

hostess. Johnson documented African-American life in Lincoln

in the early 20th century. JOHN JOHNSON, Courtesy Douglas

Keister

After this John Johnson photograph

was featured in Newsweek magazine in November 1999, collection

owner Douglas Keister received a call from a radiologist in

Atlanta, Ga. The man, Jim Zakem, said the child on the far left

was his father, James. Zakem's grandfather, Lebanese-born Alexander

K. Zakem (1879-1942), and his wife Anise had three children.

James, born in Michigan in 1917, is pictured at left beside

little sister Lillian. The blond boy was a playmate. Older sister

Adeline (at right) was born in Montreal in 1916. JOHN JOHNSON,

Courtesy Douglas Keister

Manitoba "Toby" James had three

daughters and two sons. Pictured with him here are his firstborn

son, Mauranee (in the hat at right), and his daughters Myrtha

(left) and Edna (center). JOHN JOHNSON, Courtesy Douglas

Keister

This scan of a glass plate

negative by photographer John Johnson shows early Lincoln history.

JOHN JOHNSON, Courtesy Douglas Keister

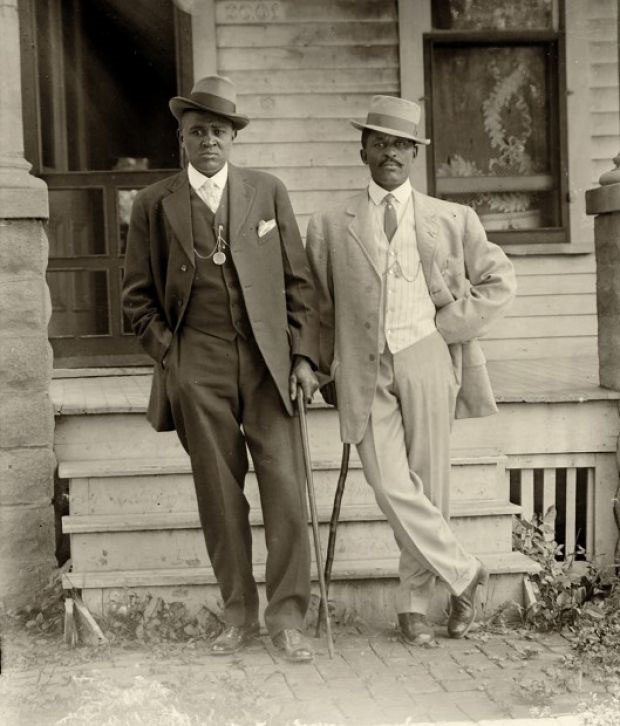

The address on the house behind

these well-appointed gentlemen suggests it was the home of George

and Fronia Butcher at 2001 U St. Butcher (thought to be the

taller man) was born in Philadelphia in 1874, and died at the

VA Hospital in Lincoln in 1958. He worked for the Chicago &

Rock Island Railroad as a porter and for Burlington as a laborer

in the Havelock Shops. Fronia Butcher was even more long-lived,

reaching 100 years (1879-1979).The dapper man with the cane

remains unidentified. The photograph is among many taken in

Lincoln on black and white glass negatives by African-American

photographers John Johnson and Earl McWilliams between 1910

and 1925.

UPDATE by Doug Boilesen: We unfortunately

didn't find an Edison Phonograph at the time of purchasing these

black and white glass negatives and have never acquired any

Edison that would be considered the holy grail of Phonographs

as reported in this newspaper article. Nevertheless, we are

honored to be a part of the story of preserving these wonderful

images and I know Dad would have loved to have read this article

and to later have seen these photos on exhibit when they finally

made their way back to Lincoln and were displayed at the Nebraska

History Museum in April 2019.

For more details about how Doug

and Axel Boilesen acquired the glass negatives, a video

was made by Doug Keister and is available HERE.

UPDATE April 15, 2020: The PBS

Nebraska Educational Televsion Station has just released their

production of this story as part of their NET "Nebraska

Stories" series. This episode is titled "Forgotten

Stories" and is really well done. Here is how it's

summarized:

"Forgotten World" His photographs

of black families living in Lincoln during the early 1900s

has made John Johnson one of the great African American photographers

of the 20th Century. All of the Johnson's work could have

easily been lost to the ages but for a teenage boy who, in

1965, spent 10 dollars to buy a box of 280 glass plate negatives.

UPDATE by Doug Keister, April

20, 2020: I continue to be astounded how my half-century journey

with the John Johnson glass negatives continues to evolve. Like

most adventures it has been a mixture of serendipity, good luck,

hair-pulling frustration, dogged perseverance, ah-ha moments

and continual heart-warming discoveries. I fully expect photographer

John Johnson and the significance of his photographs to be fully

realized as the story continues to unfold.

One major vehicle that puts the

photographs in public view is a traveling exhibition of Johnson’s

photographs arranged by Exhibit

Envoy.